400-998-5282

专注多肽 服务科研

400-998-5282

专注多肽 服务科研

Definition

Apoptosis or programmed cell death is a normal component of the development and health of multicellular organisms. Cells die in response to a variety of stimuli and during apoptosis they do so in a controlled, regulated fashion.

Discovery

In 1885, Flemming W described the process of programmed cell death. John Kerr's discovery, in late 1960s, initially called "shrinkage necrosis" but which he later renamed "apoptosis", came about when his attention was caught by a curious form of liver cell death during his studies of acute liver injury in rats 1,2. Kerr in 1972 proposed the term apoptosis is for mechanism of controlled cell deletion, which appears to play a complementary but opposite role to mitosis in the regulation of animal cell populations. Its morphological features suggest that it is an active, inherently programmed phenomenon, and it has been shown that it can be initiated or inhibited by a variety of environmental stimuli, both physiological and pathological 3.

Structural Characteristics

Heterodimerization between members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins is a key event in the regulation of programmed cell death. The molecular basis for heterodimer formation was investigated by determination of the solution structure of a complex between the survival protein Bcl-xL and the death-promoting region of the Bcl-2-related protein Bak. The structure and binding affinities of mutant Bak peptides indicate that the Bak peptide adopts an amphipathic helix that interacts with Bcl-xL through hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. Mutations in full-length Bak that disrupt either type of interaction inhibit the ability of Bak to heterodimerize with Bcl-xL 4.

The structure of the 16–amino acid peptide complexed with a biologically active deletion mutant of Bcl-xL was determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). The structure was determined from a total of 2813 NMR-derived restraints and is well defined by the NMR data. The Bak peptide forms a helix when complexed to Bcl-xL. The COOH terminal portion of the Bak peptide interacts predominantly with residues in the BH2 and BH3 regions. Melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis (ML-IAP) is a potent anti-apoptotic protein that is upregulated in a number of melanoma cell lines but not expressed in most normal adult tissues. Overexpression of IAP proteins, such as ML-IAP or the ubiquitously expressed X-chromosome-linked IAP (XIAP), in human cancers has been shown to suppress apoptosis induced by a variety of stimuli. X-ray crystal structures of ML-IAP-BIR in complex with Smac- and phage-derived peptides, together with peptide structure−activity-relationship data, indicate that the peptides can be modified to provide increased binding affinity and selectivity for ML-IAP-BIR relative to XIAP-BIR3 5.

Mode of Action

Upon receiving specific signals instructing the cells to undergo apoptosis a number of distinctive changes occur in the cell. Families of proteins known as caspases are typically activated in the early stages of apoptosis. These proteins breakdown or cleave key cellular components that are required for normal cellular function including structural proteins in the cytoskeleton and nuclear proteins such as DNA repair enzymes. The caspases can also activate other degradative enzymes such as DNases, which begin to cleave the DNA in the nucleus.

Apoptotic cells display distinctive morphology during the apoptotic process. Typically, the cell begins to shrink following the cleavage of lamins and actin filaments in the cytoskeleton. The breakdown of chromatin in the nucleus often leads to nuclear condensation and in many cases the nuclei of apoptotic cells take on a "horse-shoe" like appearance. Cells continue to shrink, packaging themselves into a form that allows for their removal by macrophages. There are a number of mechanisms through which apoptosis can be induced in cells. The sensitivity of cells to any of these stimuli can vary depending on a number of factors such as the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins (eg. the Bcl-2 proteins or the Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins), the severity of the stimulus and the stage of the cell cycle. The Bcl-2 family of proteins plays a central role in the regulation of apoptotic cell death induced by a wide variety of stimuli. Some proteins within this family, including Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, inhibit programmed cell death, and others, such as Bax and Bak, can promote apoptosis 6, 7.

Functions

For development, Apoptosis is as needed for proper development as mitosis is. Examples: The resorption of the tadpole tail at the time of its metamorphosis into a frog occurs by apoptosis.

Integrity of the organism, Apoptosis is needed to destroy cells that represent a threat to the integrity of the organism. Examples: Cells infected with viruses8.

Cells of the immune system, as cell-mediated immune responses wane, the effector cells must be removed to prevent them from attacking body constituents. CTLs induce apoptosis in each other and even in themselves 9.

Cells with DNA damage, damage to its genome can cause a cell to disrupt proper embryonic development leading to birth defects to become cancerous.

References

1. Kerr JF (1965). A histochemical study of hypertrophy and ischaemic injury of rat liver with special reference to changes in lysosomes. Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology, 90(90):419-435.

2. Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR (1972). Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer., 26(4):239-257.

3. O'Rourke MG, Ellem KA (2000). John Kerr and apoptosis. Med. J. Aust., 173(11-12): 616-617.

4. Franklin MC, Kadkhodayan S, Ackerly H, Alexandru D, Distefano MD, Elliott LO, Flygare JA, Mausisa G, Okawa DC, Ong D, Vucic D, Deshayes K, Fairbrother WJ (2003). Structure and function analysis of peptide antagonists of melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis (ML-IAP). Biochemistry, 42(27):8223-8231.

5. Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim D, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Eberstadt M, Yoon HS, Shuker SB, Chang BS, Minn AJ, Thompson CB, Fesik SW (1997). Structure of bcl-xl-bak peptide complex: recognition between regulators of apoptosis. Science, 275(5302):983-986.

6. Hanada M, Aimé-Sempé C, Sato T, Reed JC (1995). Structure-function analysis of Bcl-2 protein. Identification of conserved domains important for homodimerization with Bcl-2 and heterodimerization with Bax. J. Biol. Chem., 270(20):11962-11969.

7. Cheng EHY, Levine B, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Hardwic JM (1996). Bax-independent inhibition of apoptosis by Bcl-xL.Nature, 379:554-556.

8. Alimonti JB, Ball TB, Fowke KR (2003). Mechanisms of CD4+ T lymphocyte cell death in human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS. J Gen Virology., 84(84): 1649-1661.

9. Werlen G, Hausmann B, Naeher D, Palmer E (2003). Signaling life and death in the thymus: timing is everything. Science. 299(5614):1859-1863.

FAM标记说明:

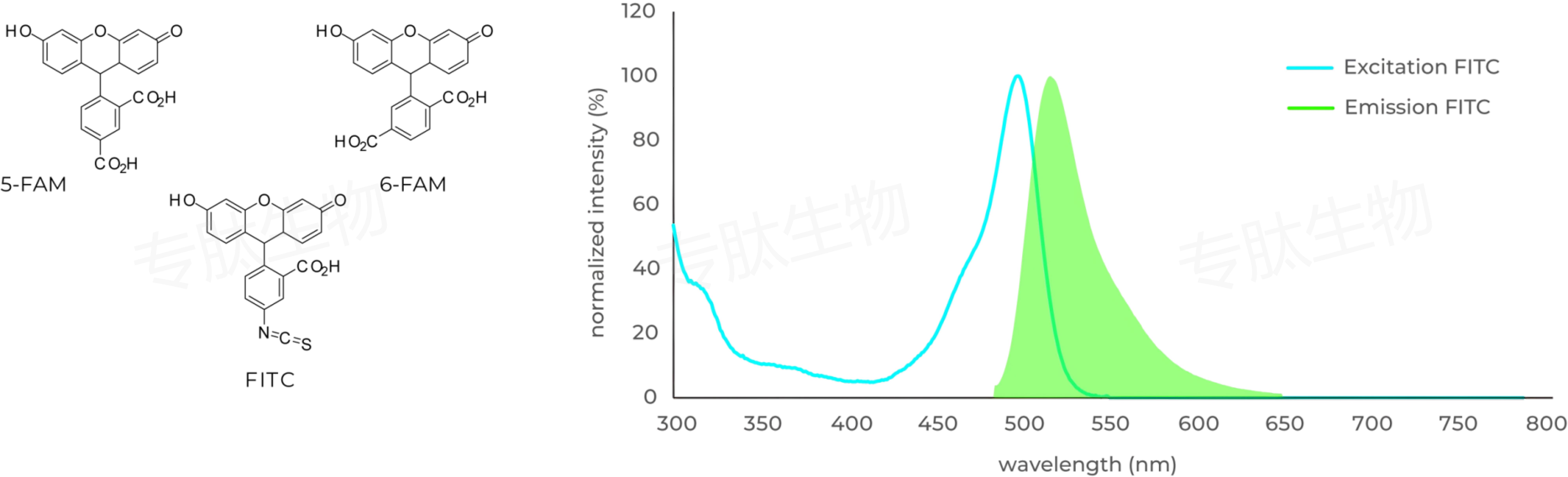

Carboxyfluorescein (FAM) is fluorophor with an excitation at 492 nm ▉ and emission of 517 nm ▉. Donors like FAM and 5FAM are often paired together with acceptors (CPQ2) for FRET experiments.

FAM标记肽的相关文献:

Porous Silicon Nanoparticle Delivery of Tandem Peptide Anti-Infectives for the Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lung Infections.

Kwon, Ester J., et al. Advanced Materials 29.35 (2017).

Ultrasensitive tumor-penetrating nanosensors of protease activity.

Kwon, Ester J., Jaideep S. Dudani, and Sangeeta N. Bhatia. Nature Biomedical Engineering 1 (2017): 0054.

Seneca Valley Virus 3C pro Substrate Optimization Yields Efficient Substrates for Use in Peptide-Prodrug Therapy.

Miles, Linde A., et al. PloS One 10.6 (2015): e0129103.

The function of the milk-clotting enzymes bovine and camel chymosin studied by a fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay.

Jensen, Jesper Langholm, et al. Journal of Dairy Science 98.5 (2015): 2853-2860.

A comparison of modular PEG incorporation strategies for stabilization of peptide-siRNA nanocomplexes.

Lo, Justin H., et al. Bioconjugate Chemistry (2016).